In the spring semester of my first year of my master’s degree at Aalborg University, I took a class on mobility called “Theories of the Network City”. Although I had only considered mobility as transportation, I realized that we consider the effect on human experiences and feelings with mobility perspective. Since I started the graduate education to study how urban design can improve the local lives, I was so impressed that I could say that I came to Denmark to take this module, even though it was a short-term intensive class for one month.

I thought it would be a shame to keep what I learned to myself, so I asked permission from Ole B. Jensen (https://vbn.aau.dk/en/persons/104214), the coordinator of the module and professor who taught us various theories and concepts about mobility. Since he has also been interested in the opportunity for research in Japan, he kindly allowed me to write this article about the lectures.

- Why Is Mobility Important in Urban Design?

- The Various Impacts of Mobility – Mobility Turn

- The Relationship between People, Objects and the City – Staging Mobility

- From Staging Mobility: Two Perspectives for Observing Human Movement – River and Ballet

- From Staging Mobility: Glasses to Recognise the Big Movements around a Place – Socialpetal and Socialfugal

- Both People and Objects Are Actors in a City Network – Actor-Network Theory

- Does the Design Hurt Someone’s Mind without Knowing It – Dark Design

- An Idea Which Exceeds the Current Restrictions Makes Innovation – Utopian Theory

- Conclusion

Why Is Mobility Important in Urban Design?

Why do we need to focus on mobility, though the urban design field usually focuses on ‘immobile things’ such as urban form and structure?

Jensen said, by focusing on mobility, we can see the connections between urban space and society and culture, which we could not see when we focused only on the form and structure (2013). It is vital to add a ‘fluid’ perspective from mobility to a traditionally ‘fixed’ perspective from urban design, instead of replacing them (Jensen, 2013).

The Various Impacts of Mobility – Mobility Turn

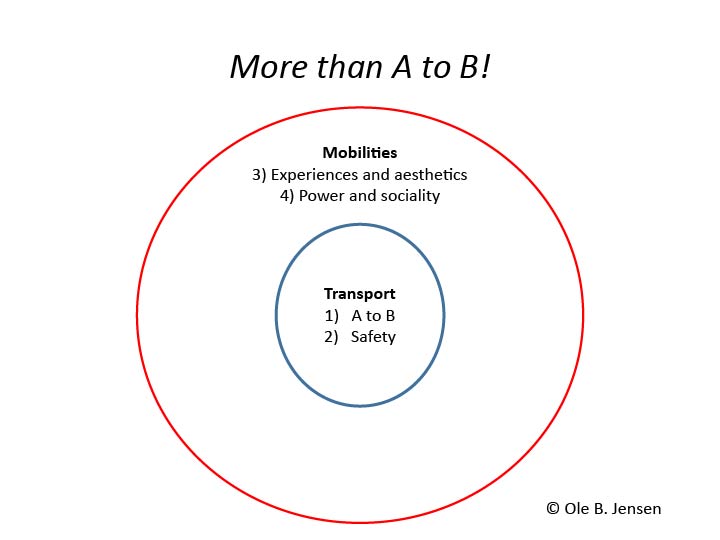

The term ‘mobility turn’, which was made by British sociologist John Urry, shows the complexity and various impacts of mobility, saying that mobility is not just about getting from point A to point B, but has physical, social, economic and cultural consequences. (Figure 1) (Jensen, 2013).

Behind this perspective, there is a change in the focus of the mobility study. Originally, mobility study belonged to sociology. However, British sociologist John Urry said in the book ‘Sociology beyond Societies’ (2000) that when sociology is used to see the society, a society is equal to nation state, but in the light of mobilities, we should say that societies are equal to relations and networks across scales. Therefore, the mobility study began to expand its field across different cities and disciplines, and the idea of ‘flow’ which includes ‘process’ and ‘speed’ becomes a focal point in mobility (Jensen, 2013).

It is interesting to note that mobility research covers not only people but also goods, information, signs and sometimes even energy (Jensen, 2013). Moreover, it investigates not only what moves in urban space, but also what constitutes the space, such as buildings and objects. (This will be explained in more detail in the section about ‘Actor-Network Theory’.)

The Relationship between People, Objects and the City – Staging Mobility

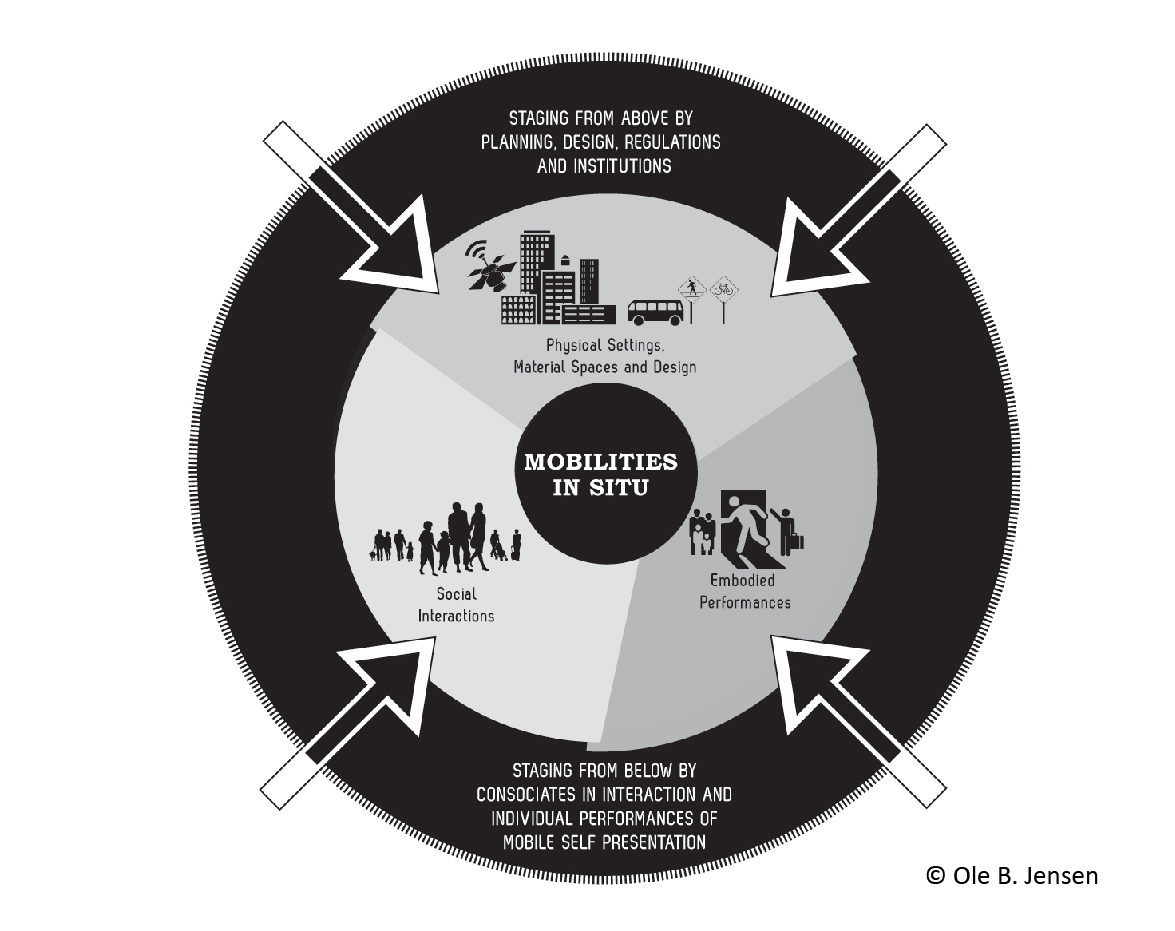

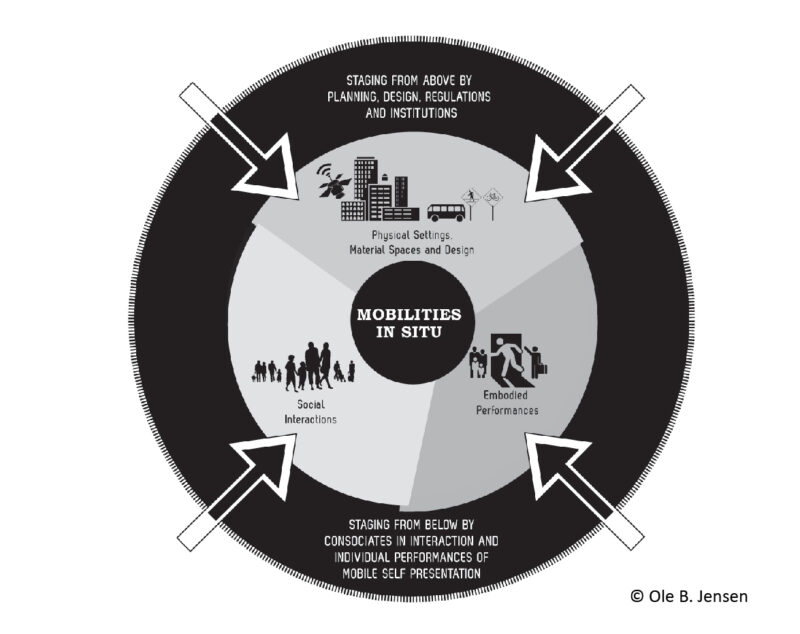

This is Jensen’s theory to rethink the relationship between people, objects and space by recognising the urban space as a stage (Figure 2) (Jensen, 2013). This theory stems from the theory of Georg Simmel, a German and one of the fathers of sociology, Erving Goffman, a Canadian micro-sociologist, and Kevin Lynch, an American urban planner and designer. (Jensen, 2013)

First of all, when we recognise the city as a stage, we can notice what is staged by people like a director (eg. streets, rules, etc.), and what is staged by people themselves (eg. the action of stopping, sitting, playing, etc.). Furthermore, the flow in the space can be observed from three perspectives: ‘Physical settings, material and design (roads, structures, buildings, and even the internet)’, ‘Social interactions (not only with people, but also with objects and technologies in the space)’, and ‘Embodied performances (Specific action, such as walking, cycling, driving, etc.) ‘.

One of the most important points in the theory is taking the physical environment into account, which is not focused on usually in sociology. It makes links between the field of mobility and design-related fields urban design (Jensen, 2013).

From Staging Mobility: Two Perspectives for Observing Human Movement – River and Ballet

Based on this perspective of staging mobility, Jensen provides 13 concepts that help us to understand the relationship between people, objects and space. Here are four of the main ones.

The first two concepts are the “river” and “ballet”, which help us to understand the movement of people. River concept sees numerous types of movement as a big flow of the space like a river, in order to get a big picture of the movement (Figure 3) (Jensen, 2013). As well as observing the quantities and direction, this concept allows observers to recognise the “deposits (cars parked on the street, obstacles on the pavement, sometimes even groups of people)” and the “riverbed (the condition of roads)” of the movement (Jensen, 2013).

The concept of ballet, on the other hand, focuses on the way each movement is performed (Figure 3). This concept was inspired by the American writer and activist Jane Jacobs’ “sidewalk ballet”, which indicates the way to observe the various interactions on city roads and targets the individual’s behaviour while they move (Jensen, 2013).

If we reflect on the staging mobilities model (Figure 2), we can also say that the concept of river fits the idea of ‘staging from above’ and ballet concept fits the idea of ‘staging from below’.

Furthermore, the interesting point is when observing from these two perspectives, the height of the observation point is crucial. If you want to get the overview of a movement with the river perspective, it is better to look at it from a higher place, such as the second floor of a building, while if you want to observe the details of the behaviour with the ballet perspective, it is better to look at it from the ground (Jensen, 2013).

In fact, in a project that followed this module, my group conducted an observation using these two concepts, and we clearly understood that what we saw was totally different depends on the height of the standing point. For example, from a high point, although we can grasp the number and directions of various types of mobilities, it is difficult to know how they move. From the ground, however, we can recognise not only their speed but also their attitude. For instance, you can see a cyclist’s helmet which was not tied, indicating that he was not paying much attention to safety.

From Staging Mobility: Glasses to Recognise the Big Movements around a Place – Socialpetal and Socialfugal

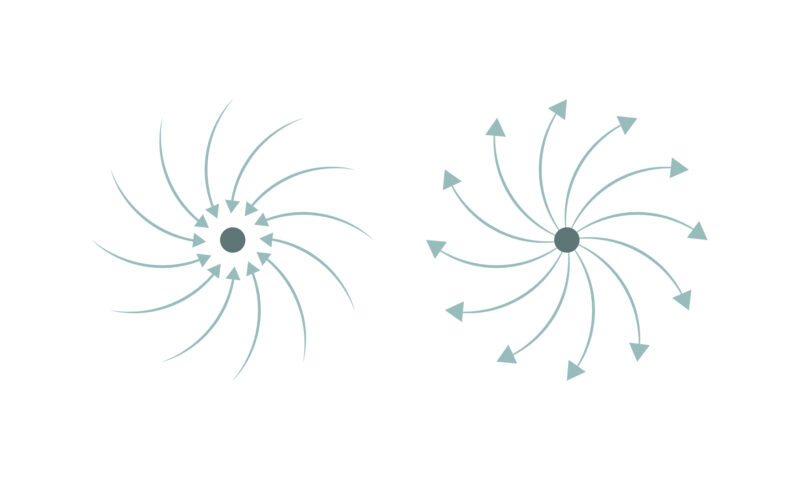

Next, I would like to introduce the concept of ‘sociopetal’ and ‘sociofugal’. This is a way of grasping the overall movement around a central place. With these concepts, we can see whether the place is diffusing the flow (sociofugal) or gathering it (sociopetal, petal meaning leaves of a flower) (Figure 4) (Jensen, 2013).

This does not mean that only either of them can be applied to a place, but sometimes both concepts can be applied to one place. For example, a large station can be seen both as a sociopetal and a sociofugal, as it attracts a large number of people, but also disperses them throughout the city. In our project, this concept was very useful in understanding the challenges of the site.

Both People and Objects Are Actors in a City Network – Actor-Network Theory

Actor-network theory is a theory that considers the diverse and dynamic relationships between immobile objects (eg. buildings and public infrastructures) and mobile objects (eg. people) in urban space. The point of the theory is treating immobile objects not as isolated ones, but as objects that affect the others and have relationships with them. (Jensen, Lanng & Wind, 2016)

Actor-network theory was proposed by the French philosopher, anthropologist and sociologist Bruno Latour, who sees any objects that occurs changes in a state of the others (eg. action) as actors, which has specific role of action (Latour, 2005).

By focusing on what it is doing actually, instead of its look or potential, we can see the relationship between the design of artefacts and human behaviour. For example, if you are walking down a narrow staircase and someone comes from the opposite direction, it would be difficult to ignore them. Then you can think that the design of the staircase encourages face-to-face conversation (Yaneva, 2009). It can be said that buildings and urban spaces are assemblages of actors and that people live among them, interacting with and being influenced by various things.

Until I studied the theory, in fieldwork I often ended up recording the location and design of pavements, stairs, benches, etc. After studying the theory, however, I pay attention to their actual function, and then I become able to observe experiences of people who use these spaces in an objective way.

Shinto is the indigenous religion in Japan and believes that everything has a spirit. This allows the Japanese people to have an idea of animating immobile objects and increases the unique culture of animation and manga. Although Actor-network theory just says objects reflect the intention of persons who made them and does not say objects have their own intentions, the unique theory that different objects made by different people in various ages are placed at a certain place, reflecting people’s intention, and create a diverse connection at every time gave me a new vibrant and dynamic perspective for a city.

Does the Design Hurt Someone’s Mind without Knowing It – Dark Design

Dark design, which can be said as a concept that is included by Actor-network theory, is the design in urban spaces that excludes certain groups of people (Jensen, 2019). The word ‘dark’, which stems from the social sciences to describe the specific power and social exclusion, is applied to the field of mobility by Jensen (Jensen, 2019).

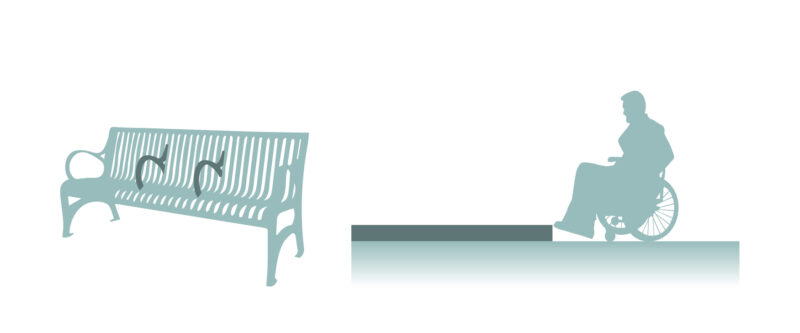

Examples are benches which are divided in a short distance by armrests (Figure 5) and protruding objects on road, preventing homeless people from staying. Dark design applies not only when access is deliberately cut off for a particular group of people, but also when access is unintentionally cut off (Jensen, 2019). For example, when a step makes it impossible for a person in a wheelchair to get through, it becomes dark design for them (Figure 5) (Jensen, 2019). Since it works directly on the user’s body, it can send a more powerful message than words in a signboard (Jensen, 2019). (Dark design can be found not only in physical design, but also in the design of transport systems. This article focuses more on physical design which is more related to urban design).

Peter-Paul Verbeek, a Dutch philosopher in the field of technology, says that even though objects do not have their intentions, they reflect the intentions of their creators (Verbeek, 2005). Verbeek call designer’s attention to artefacts in urban space, because artefacts can be seen as a reflection of moral in the local community (Verbeek, 2005).

It may be difficult to make a design that is not dark for everyone, but at least it is very important in the design process to think about the message which the design will give to others.

An Idea Which Exceeds the Current Restrictions Makes Innovation – Utopian Theory

Here we can think of the ‘flow’ as the ‘flow’ within a time axis. Utopian Theory is the idea that drawing up a detailed ideal future helps people to find a path to get there, breaking what we think it’s impossible and creating innovations (Friedmann, 2002; Jensen & Freudendal, 2012). It has been applied to fields such as urban planning since the 1970s by the French Marxist sociologist Henri Lefebvre (Jensen & Freudendal, 2012).

Although ‘Utopia’ is originally derived from a Greek word meaning ‘non-place’, John Friedmann, a community and regional planner, gives several reasons why Utopian Theory is not just a dream nor an optimistic idea. First of all, the idea from Utopian Theory is based on current issues. Secondly, the precise future visions can arouse discussion including a wide range of people, such as citizens, indicating the potential to become political action (Friedmann, 2002). Since Urry recognises the difficulty of predicting the future due to the complexity of its components, he recommends creating multiple scenarios (Urry, 2016). Precisely, people need to create not only the most ideal future, but also the logically feasible and highly likely futures (‘the probable, the possible, and the preferable’ futures (Urry, 2016). Therefore, even if the plan doesn’t go as expected, we can still make flexible choices to make a better future.

At first, I thought ‘If we imagine the future which is far from the current situation, it seems like a waste of time’. However, I became aware of its importance when I read the words of the British geographer David Harvey, who said that, as a ship targeted for port, ‘without a vision of utopia there is no way to define that port to which we might want to sail’ (Jensen & Freudendal, 2012), which indicates that the necessity of future visions to create a better society. The importance of Utopian Theory was also mentioned by the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels (Jensen & Freudendal, 2012), who is also involved in the urban development plan in Higashi-Fuji in Susono City, Shizuoka Prefecture in Japan.

When I worked as an urban landscape consultant, I used to think about what I could do within the limitations of the law and regulations first and foremost, and I thought it was creative to come up with the best ideas within those limitations. Therefore, the idea of drawing an ideal situation without considering any limitations was a shock to me, and I was delighted to be taught such a bold attempt in an academic field.

What I associate with Utopian Theory is alchemy. Even though it is not possible to make gold from non-metals, in the process, people discovered phosphorus and nitric acid etc. and contributed to the great development of chemistry. Like alchemy, I thought there will be unexpected great benefits in the process of pursuing the ideal future.

Conclusion

Out of the 12 lectures, I selected some of the most memorable parts. I’m sad that I can’t write about all of them, because there are many more interesting theories and concepts, such as the theory of “Critical Points of Contact (CPC)” to consider the tipping point of a junction which consists of different types of network (Jensen & Morelli, 2014), research on how the design of artefacts in public spaces can create communication between strangers (Wind & Jensen, 2019), and volumetric thinking including the idea for three-dimensional zoning using drones (e.g. changing regulations according to the time of day) (Sipus, n.d.; Jensen, 2016). Through all the classes, I was very encouraged by the fact that there is so much research on the relationship between the design of urban space and human experiences.

It was very interesting that we can recognise mobility as a flow, not only a flow of people and objects at a certain point in time but also a flow of change of a city over time. Furthermore, the perspective that a city consists of various kinds of networks (Jensen, 2013), provided me with a new perspective to see the city.

When I was working as a landscape consultant, I was impressed to hear that originally there was no good nor bad colour, and it depended on the relationship with the surrounding colours. Therefore, I deeply agreed with Jensen’s statement that urban design is a design of relationships.

Based on what I have learnt in this module, I would like to further explore how urban design, which affects various people, can create better experiences.

References

Friedman, J. (2002) The Prospects of Cities, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Jensen, O. B. & M. Freudendal Pedersen. (2012) Utopias of Mobilities, in M. H. Jacobsen & K. Tester (eds.) (2012) Utopia: Social Theory and the Future, Farnham: Ashgate.

Jensen, O. B (2013) Staging Mobilities. Taylor and Francis.

Jensen, O. B & Nicola Morelli (2014) ‘Critical Points of Contact‐Exploring networked relations in urban mobility and service design’. Danish Journal of Geoinformatics and Land Management. 46(1), p36-49.

Jensen, O. B. (2016) Drone city – power, design and aerial mobility in the age of ‘smart cities’. Geographica Helvetica. [Online] 71 (2), 67–75. Available at: https://gh.copernicus.org/articles/71/67/2016/ (Accessed: 9 July 2021).

Jensen, O. B., Lanng, Ditte Bendix. & Wind, Simon. (2017) ‘Mobilities Design: On the way through unheeded Mobilities spaces’. in: URBAN MOBILITY – ARCHITECTURES, GEOGRAPHIES AND SO-CIAL SPACE: Proceeding Series 2017:1. Bind 2017:1 Nordic Academic Press of Architectural Re-search, 2017. pp. 69-84.

Jensen, O. B. (2019) ‘Dark Design’. Mobility Injustice Materialized, in N. Cook & D. Butz. (eds.) (2019) Mobilities, Mobility Justice and Social Justice, London: Routledge, p 116-128.

Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the social. An introduction to Actor-Network-Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mitchel Sipus (n.d.) Social Robotics [online]. Michel Sipus. Available at: http://www.sipusdesign.com/drone-zoning-1 (Accessed: 9 July 2021).

Simon Wind & Jensen, O. B (2019) ‘Feedback Urbanism at Play: Formation of Publics through Playful Friction in Urban Interfaces.’ In Urban Interfaces: Media, Art and Performance in Public Spaces, edited by Verhoeff, Nanna, Sigrid Merx, and Michiel de Lange. Leonardo Electronic Almanac, 22(4).

Urry, J. (2000) Sociology beyond societies : mobilities for the twenty-first century. London: Routledge.

Urry, J. (2016) What is the Future?, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Verbeek, P-P. (2005) What things do. Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design, University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press

Yaneva, A. (2009) Making the Social Hold: Towards an Actor-Network Theory of Design. [online]

This article was translated based on “Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)” first and was modified by Asami.